Zusammenfassung

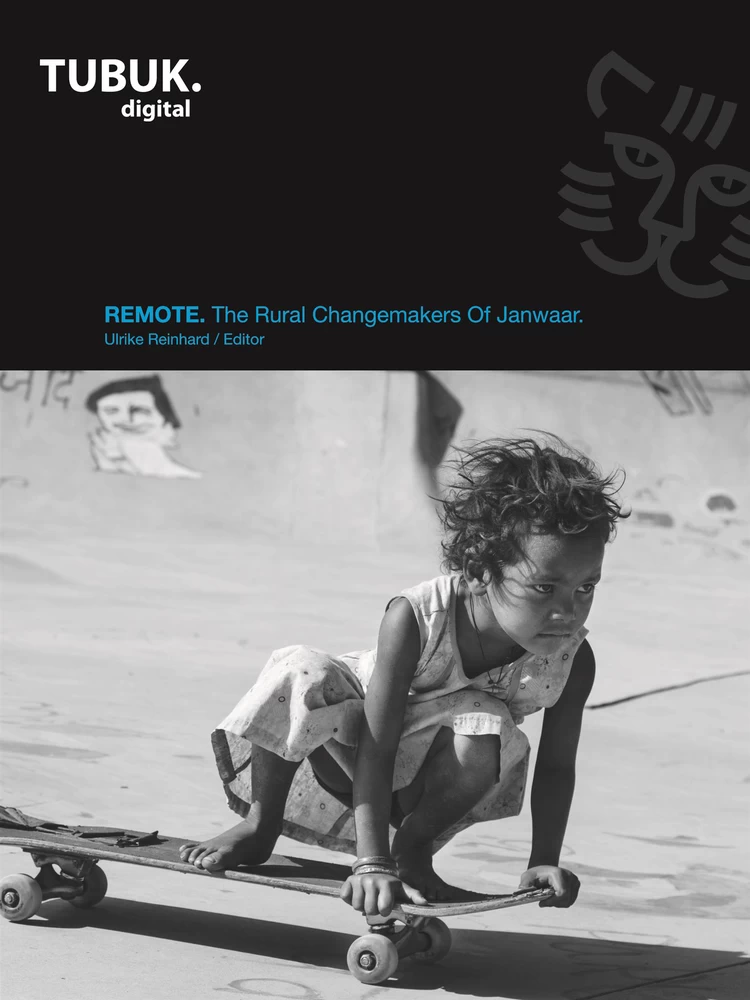

All her work is related to network theory with the Internet at its core. On these grounds she started Janwaar Castle in 2014. It was a social experiment – a skatepark in a rural village in the heart of India. What unfolded then is an incredible story of change. Social, cultural and economic change. The children in this village became true changemakers. They took the lead and became role models for many others. Skateboarding has given them selfconfidence and self-esteem. Now they are on their way to take their future in their own hands. They’ve an identity they earlier couldn’t even think of.

In this book the changemakers themselves tell their stories of change. So do their parents and people Ulrike has worked with.

Leseprobe

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Remote.

The Rural Changemakers Of Janwaar

Ulrike Reinhard

The project ‘The Rural Changemakers of Janwaar’ is the quintessence of my life. It was never meant to be like this, but looking back I can see that in some very interesting way it has connected many dots throughout my life. This is a journey which has never been a steady straight line forward but rather a story which evolved gradually and organically and in which intuition, empathy and the art of letting go played an essential role. A journey which has ended for the moment in a small remote village in India. India, a country so full of harsh and irritating extremes, a country so overburdened with disagreeable traditions and realities – and yet, surprisingly, one I fell in love with.

India and me

It wasn’t love at first sight when I first came to India in February 2012. I arrived in Delhi for a conference and I remember how relieved I was to leave after five days. The city was way too big for me, too dusty, crowded and dirty. And it was icy cold. I had no clue about India and I came completely unprepared. So when the conference was over I looked at the map. My return ticket to Germany was out of Bombay – I always call the city by its old name, I simply love the sound of it – and I was looking for an interesting land journey to reach the megacity on the Arabian Sea. Bombay and seeing India Gate was a childhood dream of mine. And I was very much disappointed when I finally did. The area looked and felt like a stronghold – the surroundings must have completely changed after the 2008 terror attacks. You couldn’t reach the gate – it was secured with heavy metal crash barriers and thousands of tourists were competing for the best view. And of course where ever tourists are in India, especially western tourists, you’ll always find a huge milling local crowd of merchants, tour guides, wheeler-dealers and hucksters of all kinds surrounding them, trying to take a gullible tourist for a ride. These were my first and none too favourable impressions of India’s two megacities.

The journey in between though was amazing. I visited the Taj Mahal and I was blown away by its sublime beauty. It was stunning. My first view was from the other side of the Yamuna river in the late afternoon. It was slightly foggy which only added to its beauty. With the orange-red sun setting on the horizon – and surprisingly no people around – the ivory-white marble mausoleum looked like a painting. Delightful. Elegant. Magnificent. The next day, at the crack of dawn I entered the gardens – and when I stood right in front of this monument it looked even more beautiful. I did what I had been told to do and walked seven times around the mausoleum anti-clockwise. Then I sat down at the far corner of the terrace and fell asleep. It was a deep but short sleep and when I woke up I left the gardens full of energy and in high spirits. They were crowded by then.

From Agra I took a train and a car to Khajuraho. In Khajuraho – yes, it took me more than a year to pronounce the name of this small village in Madhya Pradesh more or less correctly – I got stuck. No, not because of its world famous Hindu and Jain temples but because of the rough, wild, innocent and largely untouched landscape in which it’s located. No wonder the temples were built there 1000 years ago. Forests – or jungles as the locals call them, the rocky river Ken with all its caves and waterfalls, dry landscapes with scattered trees, a deep blue sky and all the wild animals have attracted me ever since. And it’s precisely this setting which made me choose Janwaar for my social experiment two and a half years after first setting foot on the subcontinent. Janwaar is just a stone’s throw from Khajuraho – yet luckily far enough away for it not to feel the negative impact tourism has.

During my first visit to Khajuraho I met a family who really put a bee in my bonnet. They “invited” me to build a school in Khajuraho on their land. I was as much surprised by such an offer as I was tempted to accept. From Bombay airport I sent an email to my friend Egon Zippel in New York asking him: “Do you want to build a school with me in rural India?” And he staggered me by immediately answering: “Yes, why not?”

A few weeks later both of us returned to Khajuraho to figure out our options. We were fascinated and starry-eyed we decided to give it a go. One of our first activities after getting acquainted with our new environment was “A Hole In The Wall”. We installed two of Sugata Mitra’s self-learning environments at the government school in Khajuraho – right by the junction where the old and new parts of the village meet. These learning stations are still up and running today, though shabby and much worse for wear. The construction work gave us a glimpse of what it means to build something in India. We probably acted like greenhorns as we painfully slow adjusted to Indian time and working standards.

At the same time we were reading a lot about the Indian or should I rather say the “leftovers” of the British education system, and we were visiting many schools. Our idea of our own school took shape and we were eager to get the “promised land” from the family. Unfortunately our plans didn’t quite meet the family's expectations. While our idea of a school was more one of informal learning and creative processes, their plan was to make tons of money out of it. Simply to get a slice of the booming education market in India which is a multi-billion dollar industry. Charity – as they had said earlier – was no longer the name of the game. Over three months we had interminable discussions which led absolutely nowhere so we finally decided to move on without them. Our last meeting took place in the reception hall of their hotel. All of a sudden the father of the two guys we were dealing with stood up, left the hall and came back with a rifle in his hands. He positioned himself right next to me and stood there like a sentinel – legs apart and the rifle poised between them. It was hilarious and grotesque at one and the same time. And I still don't know what he wanted to express with his posturing. Anyway, we simply ignored it. But it left us wondering. Finally we left their place and started anew. This was a decision they didn’t like at all. And what’s more – as we heard later – one which they weren’t used to being served. It turned out that this family was very feudal and notorious for luring in foreigners and taking advantage of them. Luckily we had an inkling of this – even though it took us a while to read their faces.

Our “divorce” was highly unpleasant and ended in a trial. Their eldest son physically assaulted me, leaving me in need of hospital attention so I took him to court. And I won. Many people were happy because this was the very first time that this family had been taken to task for their wrongdoing. The lawsuit was quite amazing – it took place in Raj Nagar, a district of Khajuraho and it dragged on for an incredible four weeks. I don’t know how many times we went there in vain. Sometimes the culprit didn’t show up, sometimes it was the prosecutor or the judge himself who were notably absent. The only guy who was happy about this was the tuk-tuk driver we’d hired for the duration of the trial. During these four weeks I had 24/7 security guards. The local head of police wanted to ensure my safety. Maybe he expected further attacks from the family – I don’t know. So where ever I went two armed police guys were ten feet behind me. This was quite funny at first but after a while it became pretty annoying.

The courtroom was small and very crowded. The judge, the prosecutor and all the people working there shared this tiny slightly dilapidated place. Its door was always open for a constant flow of people coming and going. The lawyer of the family questioned me for a full eight hours. All of us had to stand in front of the judge who was sitting behind a huge table on his high chair. Of course I was somewhat nervous at the beginning but after a while I understood the game and started to play as well. Then it was fun. Egon, as a witness, went through the same rigmarole – he made it in six hours though. In front of the courtroom was the daily market – the colours, the smells and all the different kinds of people were not what you would normally expect from a “court”. Once in a while cows even tried to push their way in. Living through all this taught me a lot about the social fabric and dynamics of a village in rural India and helped me to get a better understanding of the family structures, the feudal system and the system of bribery in this part of the world. And it prepared me well for my future endeavours. After that lawsuit Egon and I were both ready for a break in Europe.

Egon never returned to India. The stinking garbage piles, the blatant corruption the all-pervasive feudalism, the tobacco spitting men, the never ending honking of all kinds of vehicles and the shocking discrimination of women were far more than he was willing to handle. I stayed for a few weeks back home in Germany, then I came back and started to travel through India on my trusted Bullet motorbike. I was on the road for almost a year and went from deep down south all the way up to the Himalayas where I spent the summer of 2013. And every now and then I returned to the Ken river.

An idea takes shape

One day Shyamendra Singh aka Vini, a local rajput (from the Sanskrit raja-putra meaning “son of a king”) and owner of the Ken River Lodge, asked me if I wanted to work on “his” side of the Ken river – meaning not the Khajuraho but the Panna side. He was familiar with what I’d been through in Khajuraho and I assumed that this prompted him to say: “Whatever you do, I will secure the land.” Two weeks later I made him a proposition: “Let’s build a skatepark!” “What on earth is a skatepark?” he asked. I showed him a video from Skateistan (an NGO which uses skateboarding as a medium for change) and he immediately said: “Yes!” The decision was made within five minutes in the beautiful Ken River Lodge treehouse overlooking the river Ken. Vini introduced me to a guy in Panna who owned several plots of land and without any hesitation I opted for the plot he had in the tiny little village of Janwaar. At the same time I also started the SKATEBOARDS/ARTBOARDS campaign to raise funds. I asked 15 artists from around the world, including some local artists and children from a village on the Haryana/Rajasthan border, to transform skateboard decks into ARTBOARDS. Then I auctioned these ARTBOARDS on ebay – skate-aid e.V. in Germany allowed me to do this on their platform – and with the proceeds I was able to build the skatepark. Skate-aid e.V also connected me to a German skateboarder, Baumi Baumsen who later became head of construction in Janwaar. In December 2014 we started to build India’s (and most likely the world’s) first skatepark in a rural area. 12 skateboarders from seven different nations volunteered and together with local helpers they finished the park in three and a half months. It was during the construction period that we came up with its name: Janwaar Castle.

The villagers had no idea what we were building. For sure they were wondering. For some of them it meant a chance to work and earn some money. An opportunity they don’t get all that often right on their own doorsteps. Others were afraid – as I heard later – that I would “christianise” their village. Three or four weeks after construction started I felt some strange dynamics and asked Lokendra Singh, the Maharaj of Panna, and I think I can say a friend of mine, to come and see what was cooking. He is truly a character. Over the years I’ve learnt to value his “one-liners” with which he precisely encapsulates situations in Indian society. More than one hundred villagers showed up at the skatepark when he came. They gathered around him while he was talking to them. Once in a while he asked me a question which I answered the best I could. I somehow felt lost and had no idea what was going on. When he said “chalo” I went back with him to the car and we left. On our way out he didn’t say much. No way would he tell me what the discussion was all about – but the one-liner came as expected and I will never forget it: “You haven’t won their hearts yet!” This stuck with me and really made me think. I believe this incident laid the groundwork for the strong personal relationships I have today with many of the kids and quite a few of their parents – even though I don’t speak their language there is this basic and very precious mutual understanding.

The bare fact that I don’t speak Hindi – and I don’t have any ambitions to learn it – is a very conscious decision I’ve made. It provides me with a “natural border” and protects me from getting involved in every tiny little detail of village chit-chat. Not that speaking and understanding Hindi wouldn’t help me in many instances … but still you can’t have it all!

This book features many photos of Janwaar. Looking at them, you can easily get an idea of how sleepy and badly developed Janwaar is. It’s a small village of 150 households in a remote area of Madhya Pradesh. From Delhi it takes a night train, a bus (2.5 hours) and a “tuk-tuk” (20 minutes) to reach. And the next big town, Panna, is seven kilometres away and has no real restaurant, only street food. The first tiny little supermarket arrived two years ago and for many tools and other things we need to go to Satna (70 kilometres away) or even Jabalpur (250 kilometres). So it’s an almost surreal setting in which to see a skatepark, isn’t it? The one basic question I asked myself about this social experiment in building a skatepark in the middle of nowhere was: Could it trigger change in such a very traditional almost untouched village? Today I can confidently answer: Yes, it can! And I would even go one step further and argue that only skateboarding can. No other sport would have achieved the same results. Why? I think it’s a cultural phenomenon. Skateboarding culture is counterculture! It’s almost a synonym for “against the mainstream”. It’s all about disobedience, resilience, finding your own way. Exactly the opposite of what went on in this village. And because of this I was pretty sure that something would happen in Janwaar once the skatepark was in full swing.

Sleeping outside in the courtyard at Arun's Homestay. Photo by Vicky Roy.

The Janwaar Castle skatepark – view from the Bamboo House. Photo by Vicky Roy.

Connecting the dots

Since my early days at university in the late seventies where I studied economics in Mannheim, Germany, I have always been drawn to this idea of using management tools to solve social issues. My mentor Professor Dr Hans Raffée called it “social marketing” and this idea has stayed with me until today. 15 to 20 years later the Internet has immensely broadened such possibilities, and under the guidance of Professor Dr Peter Kruse, a neuroscientist and network theory expert with whom I worked for almost a decade as a freelancer, I learned how to combine social, Internet and network theory. And Janwaar Castle is, so to speak, a product – the outcome – of all of this.

My key idea with Janwaar Castle was to engineer change – social, cultural and economic change. Such change is to be achieved through involving the entire village community, including the children and young people in skateboarding which grows their confidence and self-esteem, extends their education, and encourages them to become role models for change within their own village. The vision is one of rural changemakers uplifting the life of the entire village.

So how to trigger this change was the crucial question. The skatepark itself was meant to play the role of a disruptor and attractor. Disruption was needed to tip this highly traditional Indian village setting out of balance. And the disruption needs to be attractive enough to get things moving. You need momentum to achieve change. This is exactly what you’d do in a company if you were planning to drive change. What happened is that the kids started to come to the skatepark. I gave them 20 skateboards, helmets and safety gear and basically left them to their own devices. I myself can’t skateboard, so my only “help” was skateboarding videos which I showed to the kids on tablets. They loved to watch them and immediately afterwards they took the skateboards and tried to copy the tricks they’d just been watching. And it worked – the skatepark was attractive.

They were very quick on the uptake and the skatepark became our playground in which things started to flourish and from where beautiful stories emerged. Right from the beginning, the kids took ownership of, and responsibility for, the skatepark. They kept it fairly clean. They understood and felt that it was theirs! What they experienced at the skatepark was certainly different from what they experienced at home – and this was the disruptive moment. They were challenged to bridge these differences if they wanted to skateboard – and this created the momentum we needed.

Inspired by the work of Skateistan I took a slightly different approach. While the Skateistan skateparks are closely attached to a school and operate with “opening hours” – a closed system so to speak – I decided to keep Janwaar Castle as open as possible. This meant first of all no fences, no fees, no gate-keepers controlling the park. I remember the discussions I had with Vini and the owner of the skatepark land who both wanted to build a fence. They kept on insisting: “But we need a fence!” And I stoically answered: “No, we don’t!” I was more concerned with chasing the buffaloes, cows and goats from the skatepark than with building a fence. And over the years even the cattle have learnt not to clump over the skatepark. So it paid off – Janwaar Castle is accessible for everyone at any time – and the kids love it.

Secondly, “open” also means for us that we do NOT define any programs. We are open for what the kids will show us and what interests them. So we follow their lead. Skateistan offers what I call “pre-defined” programs – which isn’t wrong in itself but which is not inclusive. The program may be suitable for a few kids, no doubt, but it’s never as personalized as the individual learning paths we design for our kids. I had the same sort of discussion about this with Vini as I’d had with him about the fence. His contention was that: “We need a program! We need to know what we’ll be doing next month, next quarter, next year.” And I kept on replying: “No!”. I truly believe – and so far I haven’t been proven wrong – that all we need is a vision and a clear set of values and principles in which all our activities (= disruptions) take place. We should know what we’re aiming for. In business speak this is called the “open sandbox”. In reality it means that we observe what is happening at the skatepark and we take it from there.

I always feel that this is very much like the Internet: You cannot predict what will happen next. You have to live it! All you can do is to be as close as possible to the “playground and its actors” – only then will you get a feeling for what might come next. It’s all about empathy and letting things go.

The lakeside playground and library in Janwaar. Photo by Vicky Roy.

Villa Janwaar – our new community center in the center of the village. Photo by Vicky Roy.

If one of the Janwaar kids is “ready to move”, we try to design a very individual learning path for them and guide them on their way. So it’s not like “one program fits all”. We don’t tell them what to do, we let them do it! So once more, as in the business world, we practice “pull” not “push”. Meanwhile many kids have started to move and show us their field of interests – be it in the creative arts, music, dance, agriculture, building things or sports. Based on their interests – and together with our partners at the Prakriti school in Noida (Uttar Pradesh), Art Ichol in Maihir (Madhya Pradesh), the Kabir Foundation in Kundarpura (Madhya Pradesh) and Laxman Das Sukhraman, an organic farmer in Janwaar itself – we have designed learning labs. These learning labs are off the regular school schedule and are very hands-on. They complement what is (or is not) happening at the government school. Sometimes a lab lasts a few hours, sometimes a few days, depending on the subject. Currently they’re few in number but they’re easy to scale. The scale though is not linear, it’s an organic growth branching out in many directions. Sometimes a lab is for a single child, sometimes for a small group.

Let me give you a few examples: The sport labs include repair and maintenance of skateboards. Some of our kids are “hidden” artists. At Art Ichol’s ceramic centre they learn a lot about clay. They model tiny little skateboards which visitors love to take as souvenirs of Janwaar. This has become a steady source of income for Karan, one of our elder boys. In creative labs the kids design postcards out of plastic garbage and learn how to take photographs. Some kids have built kitchen gardens and others are learning to dance. We have a treehouse which is home to an open library and we have two playgrounds – one close to the skatepark and another at the lakeside.

The frameset of values and principles in which we operate reflects the core principles of a networked world and the changes the Internet has triggered. This realm – along with economics – is my background. I had my first email account in 1987 at “The Well”. That was a full seven years before the Internet got pictures. Back then I was living in Sausalito, California, right above the office of “The Well”, that iconic forerunner of all online communities. Regrettably, many of its successors lack its wit, vibrancy and charm, virtues The Well used to have in buckets. In those days the Internet was still in its infancy but everyone around knew that this new invention had the capability to change the world. And it did. This community and the years I spent in California had a deep impact on me. There isn’t a single project of mine which is not related to the Internet and its huge transformational power. So for me it was a no-brainer that Janwaar Castle would reflect all this in its mode of operation – and I’m even tempted to say that with Janwaar Castle we’ve created a model which shows a different yet very efficient way of practising so-called “development aid”. I hate this word because we enable and empower more than we develop – but at the end of the day this is the concept people use to describe our work.

So here are the core principles under which we operate and which we apply to each single activity we do. I’'s almost like a checklist.

Some of them I’ve already mentioned in this introduction. Others are central themes of articles in this book. So no worries, I won’t “talk” you through every single one of them. But what I want to emphasize here is that Janwaar Castle as a concept is a holistic approach. It has its deep roots in system theory – these principles interfere with and relate to each other. They are all equally important and yes, there is causality among them. Janwaar Castle is a system – just like the Internet – which plays beautifully if you let it play. A system in which the art of letting things go, intuition and empathy – as I mentioned at the outset – are key. A system like this is very robust and precious because of the strong bonds it creates among the people involved. What binds them together has an energetic cultural component. So as we move on with Janwaar Castle we create village culture. We create an identity. Something a villager or a kid can relate to. Which provides meaning. Which makes the people feel proud.

The villagers of Janwaar do feel proud. Only recently the father of Priyanka (see our story on page 74) who works for the municipality in Panna, said: “On Google, Janwaar is way ahead of Panna or Satna or any big town in Madhya Pradesh! It’s even ahead of Khajuraho!” And I sense the same kind of pride when visitors come to Janwaar and the kids show them their village, their skatepark, their homestays, their libraries and playgrounds, their Villa Janwaar, our brand new community centre. When they involve visitors in their activities and “show off” at the skatepark – these are the moments when you sense their pride. One of our visitors said: “Wow, your homestay is really so nice and clean! And the food is excellent!” Quite apart from the fact that these homestays are a significant source of income for the villagers. Another visitor remarked that he envies the stamps some of the Janwaar kids have in their passports!

Where else in the 700,000 villages in India can you find something similar?

From Janwaar Castle to The Rural Changemakers

Janwaar Castle has not only inspired the kids and the villagers in Janwaar and I am sure their stories will keep coming – it has also inspired many other young people in India and around the world. Every day I receive a flurry of emails and messages and replying to them all takes me at least one or two hours a day. But I do reply consciously and seriously because this is the way I create and “feed” my growing network. And it fills me with pride and joy that I have an incredible team of young Indians around me who help me to guide Janwaar on its way. Thank you Anveer, Apoorv, Avinash, Mannan and Vicky.

What started as an experiment turned out to be a proof of concept for a new and so far successful model of development aid. The skateboarding bug is contagious and it’s spreading! I am currently working in three other locations where I will replicate the

Janwaar model – so there is more to come. And if these locations work out – who knows, maybe we can create such a momentum that Janwaar Castle turns into a movement of “Rural Changemakers” who are proud and self-assured and ready to take their lives in their own hands. Rural Changemakers who will take the lead and guide their villages into a better future!

So, yeah, I am still very happy here in India – even though I disagree with many things and am very often annoyed by daily live issues. But overall, Janwaar Castle and its rural changemakers are so much fun and give me so much satisfaction that I have no plans to leave.

I’ve even learnt to love Delhi – now that I somehow at least know my way around in Central and South Delhi – I really love this city. In Delhi you can go on a time journey. There is hardly any other megacity in the world, except perhaps Mexico City, which presents such a rich and diverse past, such a highly complex and dynamic present and places where you can see and touch the future. A city I could really live in if only there wasn’t all that pollution …

For now I’ll stay in the jungles of Panna and continue to enjoy my daily rides on my wonderful Bullet bike “Shrini” through this landscape in all its stupendous soulsoothing beauty.

If you want to drop me a line or come for a visit, please use

hello@rural-changemakers.com. Thanks!

Ulrike Reinhard on her Bullet "towing" Ramkesh Gond. Photo by Vicky Roy.

Through The Eyes Of The Kids And Villagers

Drugha Gond “uplifted”. Photo by Gabriel Engelke.

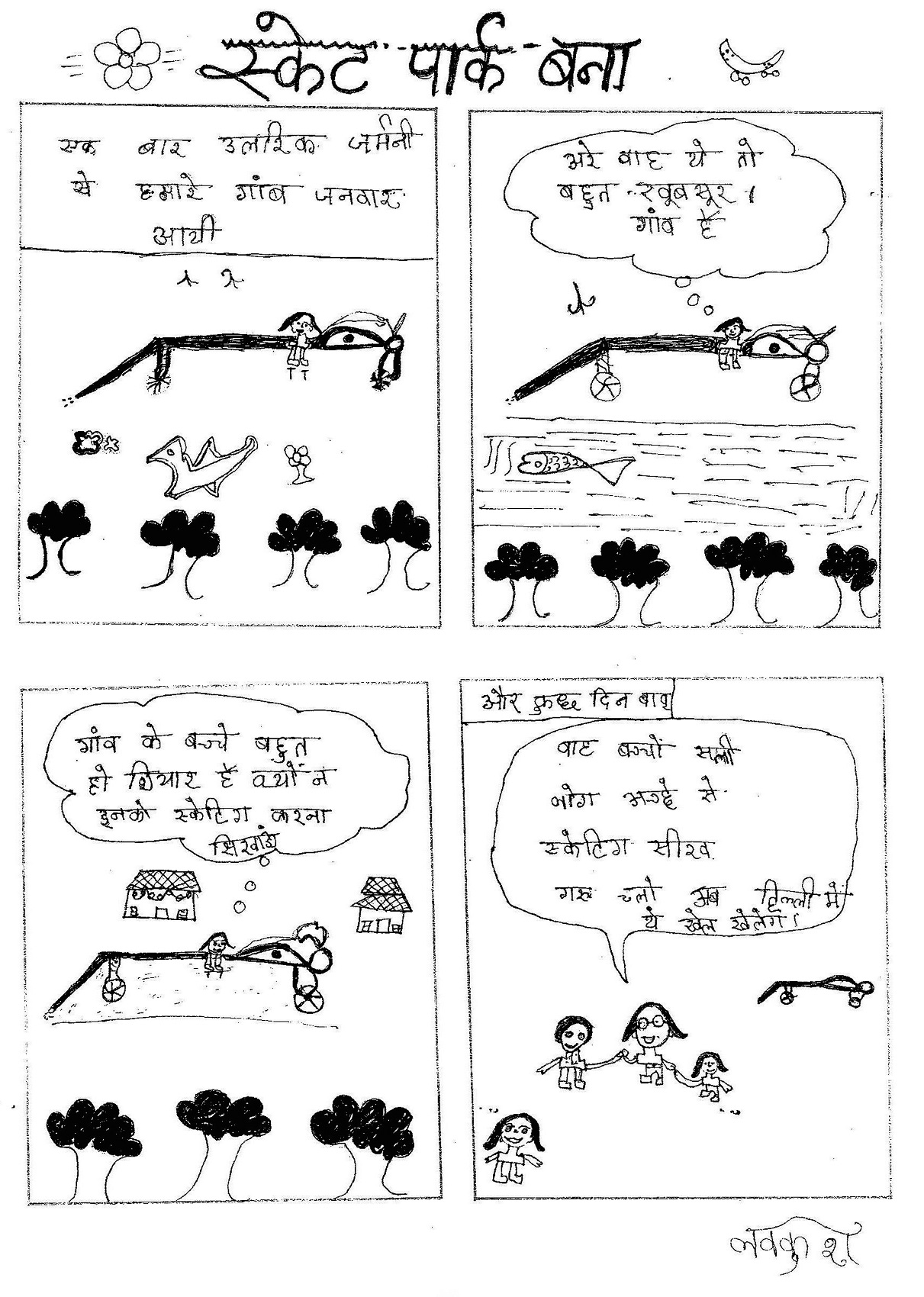

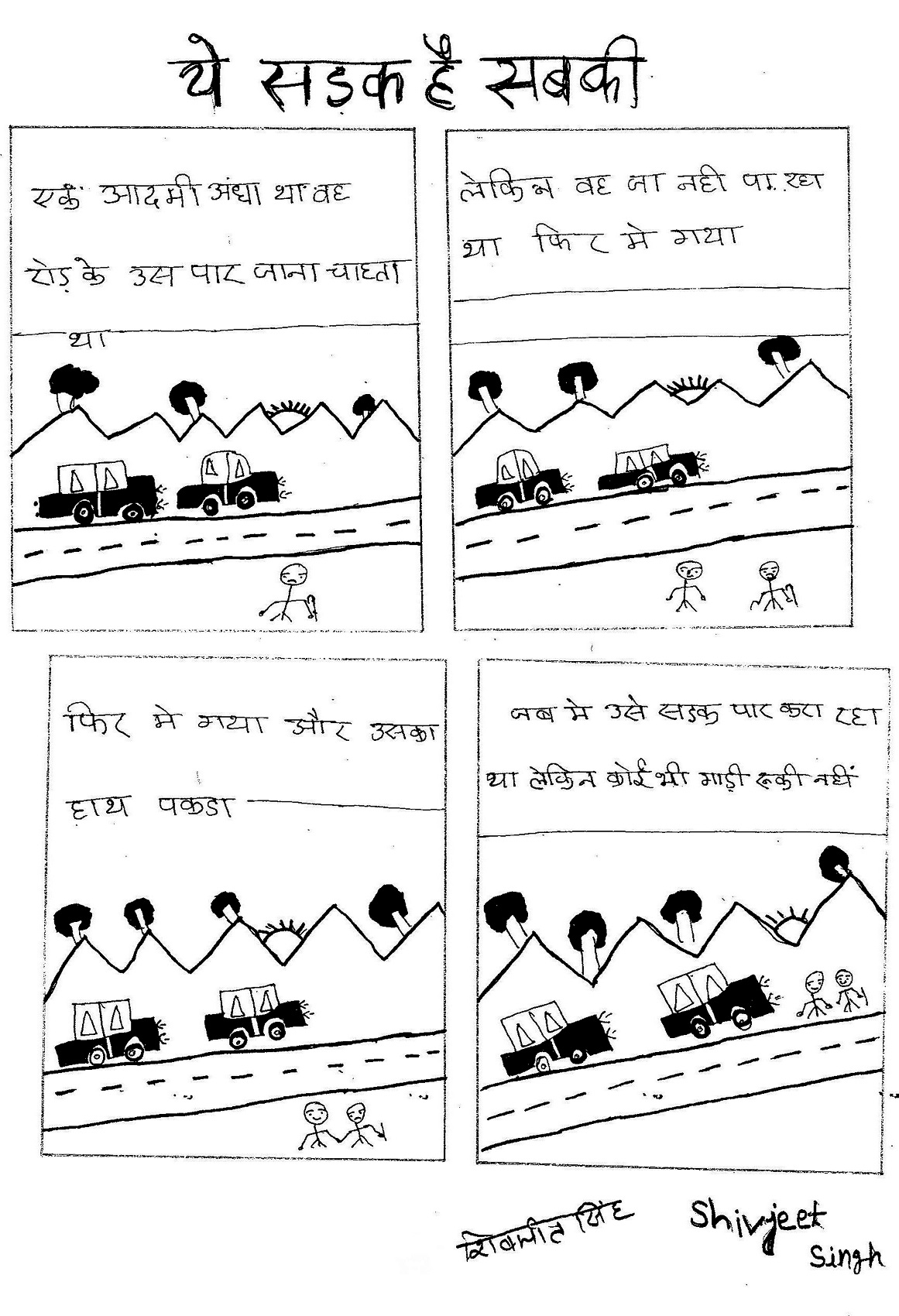

Janwaar Comic Power

Ulrike Reinhard

In November 2017 I invited Sharad Sharma, the founder of India World Comics, and his team to conduct a five day comic workshop in Janwaar. The idea was to “download” the stories around the skatepark which are hidden in the kids’ minds and to make them visible in comics. I thought this would be a very nice way to get a better understanding of how our kids think and what it is they remember.

The workshop took place in the local government school. The kids were just as excited as the teachers and were quickly drawn into the comic-making mood. First, they learnt a few basics on how to draw a comic, then Sharad explained to them how to fold a sheet into four segments and use these segments to tell the story – and then, finally, how to build up the story by matching pictures and words. It was a great exercise and the kids loved it.

At the end of day four we wrapped it up and exhibited the comic strips – first in the government school itself and then in the afternoon at a school in Panna, the closest city to Janwaar. The comic makers were very proud to show and tell their stories and once in a while also a little surprised to see how much the stories resonated with their listeners and observers.

In the meanwhile, Janwaar Comic Power has travelled to Noida and Meerut, both towns in Uttar Pradesh.

We wish you much fun diving into a small selection of the children’s comic power!

A skatepark was built – by Lavkush

Scene 1: One day Ulrike from Germany came to our village.

Scene 2: "O wow! This is such a beautiful village!”

Scene 3: "The kids in the village are very smart. Why not make them learn skatboarding?”

Scene 4: Some days later… “Wow!! The kids became pretty good at skateboarding. Let’s go to Delhi and play this game there!”

This road belongs to everyone – by Shivjeet

Scene 1: A blind man wanted to cross the street.

Scene 2: But he couldn’t do so. So I went to help him.

Scene 3: I walked towards him and took his hand.

Scene 4: But when we wanted to cross the street, no car stopped. They wouldn’t let us cross.

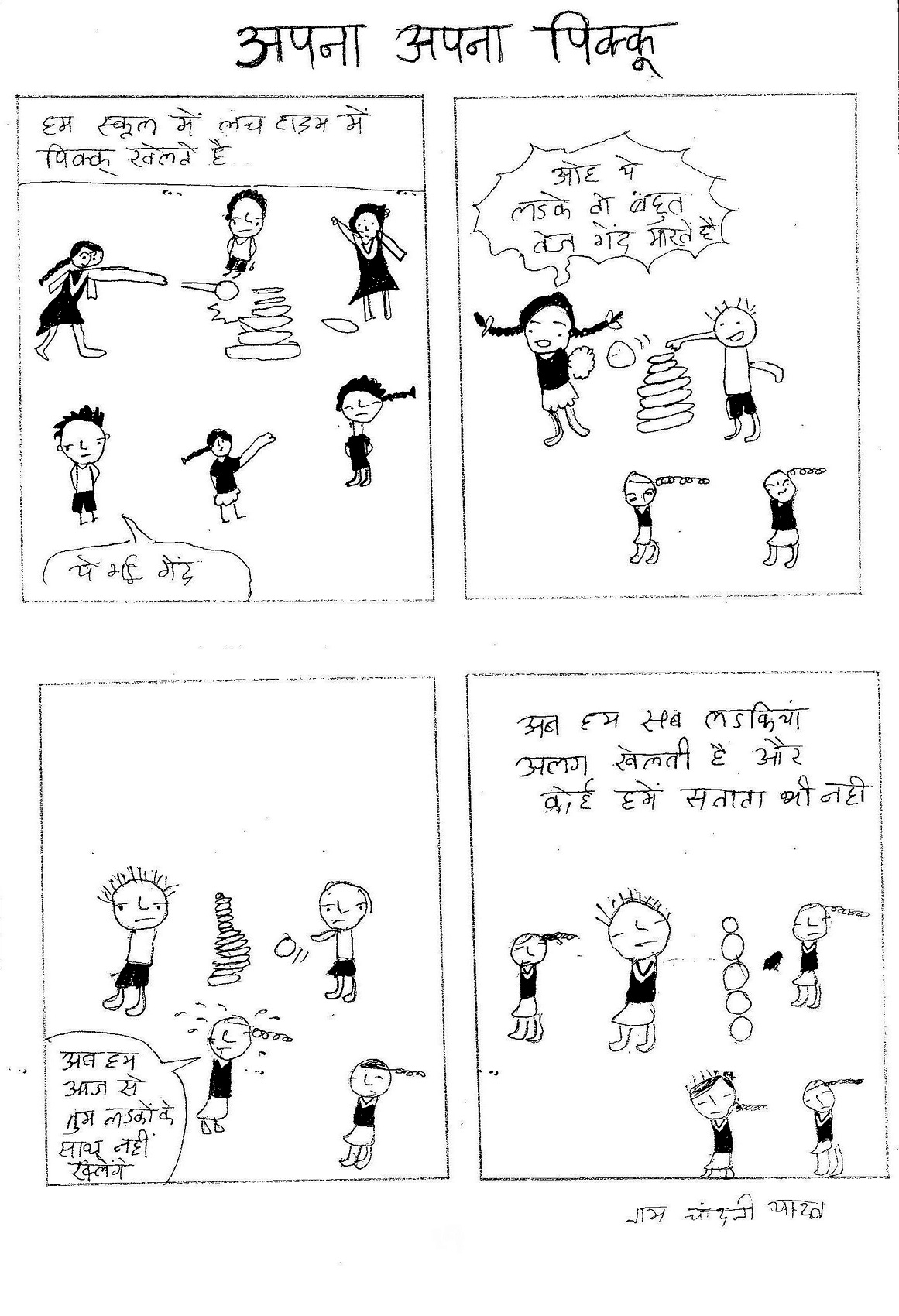

Our own Pikku – by Chandani

Scene 1: We all, boys and girls, play Pikku at school during our lunchtime.

Scene 2: Ohhh! The boys hit the ball very hard!

Scene 3: We won’t play with the boys any longer!

Scene 4: Now we girls play separately and no one is bothering us any more!

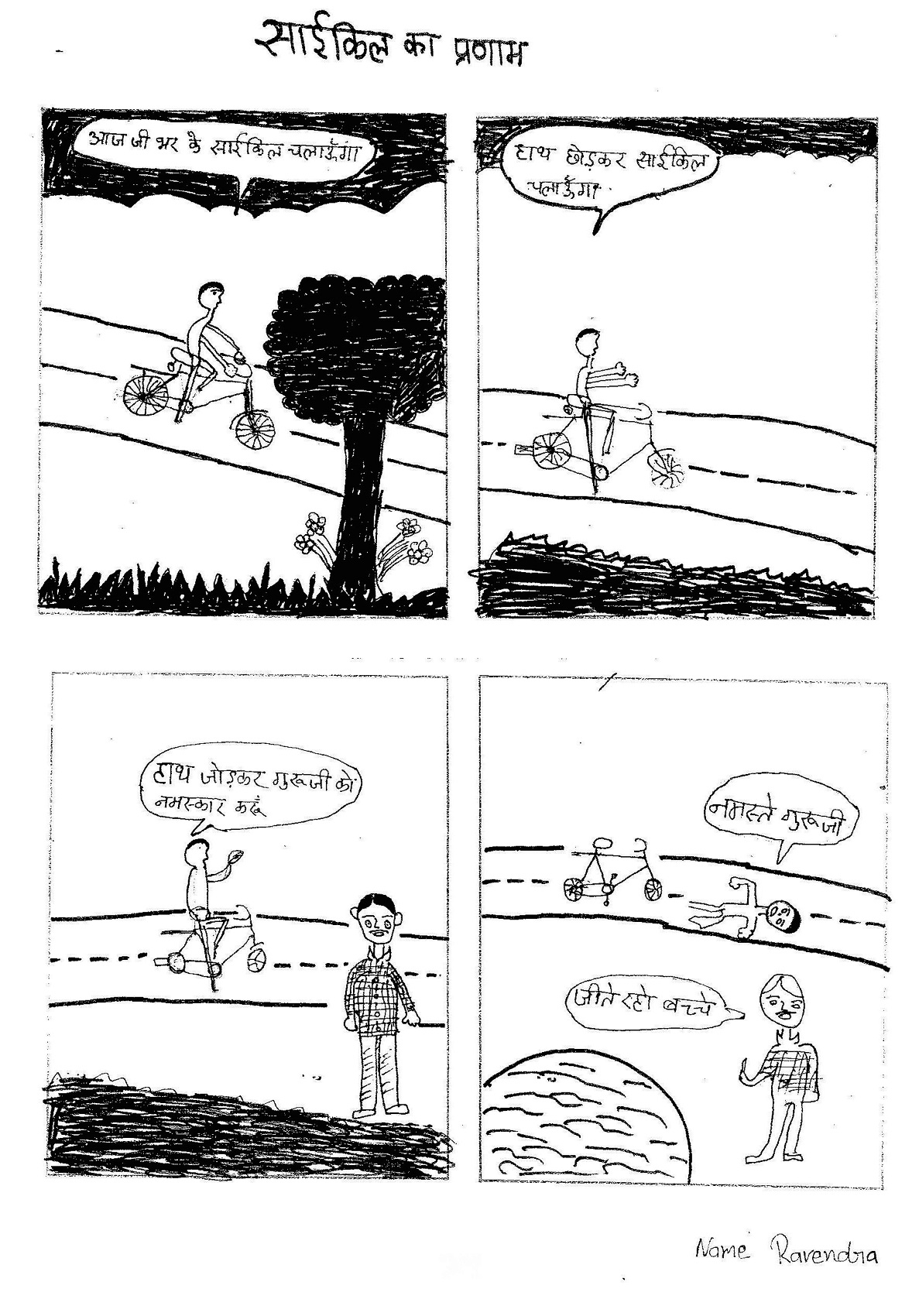

Greetings from the bicycle – by Ravendra

Scene 1: I really love to cycle today!

Scene 2: I ride my bicycle free hand!

Scene 3: I will join hands and greet the teacher.

Scene 4: “Namaste Sir!” “Long live, child!”

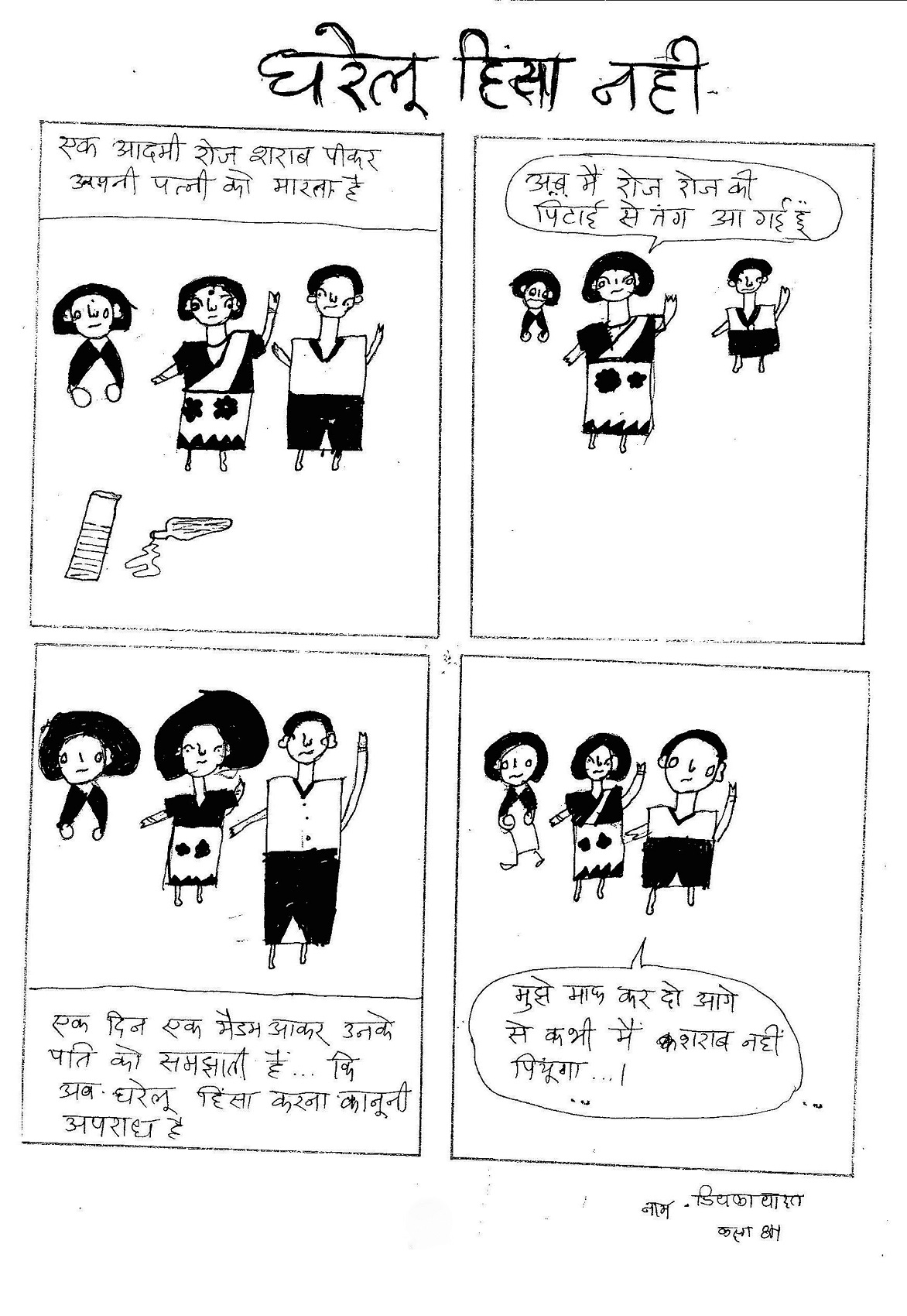

Stop violence at home – by Priyanka

Scene 1: A man used to drink alcohol everyday and then beat his wife.

Scene 2: “I am fed up with getting beaten every day!”

Scene 3: One day a madam came and explained the husband that violence at home is a crime.

Scene 4: “Please forgive me! From now on I’ll stop drinking alcohol!”

That’s how he learnt – by Neerjala

Scene 1: The water around the hand pump is causing a lot of mosquitos.

Scene 2: “Look! It’s getting dirtier every day!”

Scene 3: After some days … “See, now you’ve got sick because of a mosquito bite!”

Scene 4: “I’ve understood! From now on I’ll keep the house and the outside clean!” “Yes! Yes! Yes!”

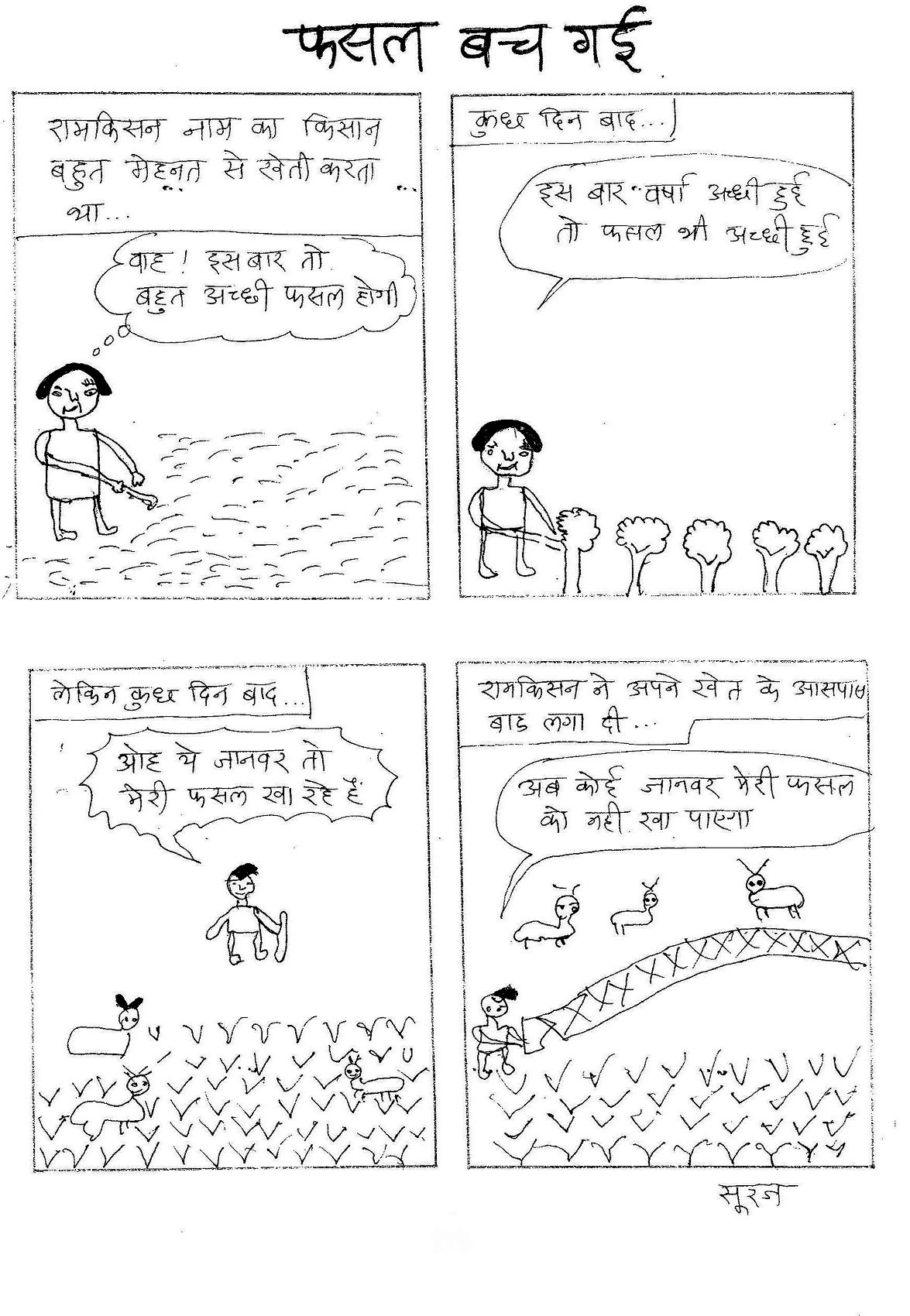

Crops were saved – by Seeraj

Scene 1: Ramkisan, a farmer, worked hard on his farm. “Woah! This year we’ll have a good harvest!”

Scene 2: After some days. “This year we had good rains and the crops were good as well. ”

Scene 3: But after a few days … “Ohhh, the animals are eating all my crops!”

Scene 4: Rankisan made a boundary around his farm. “Now no animal will eat my crops any more!”

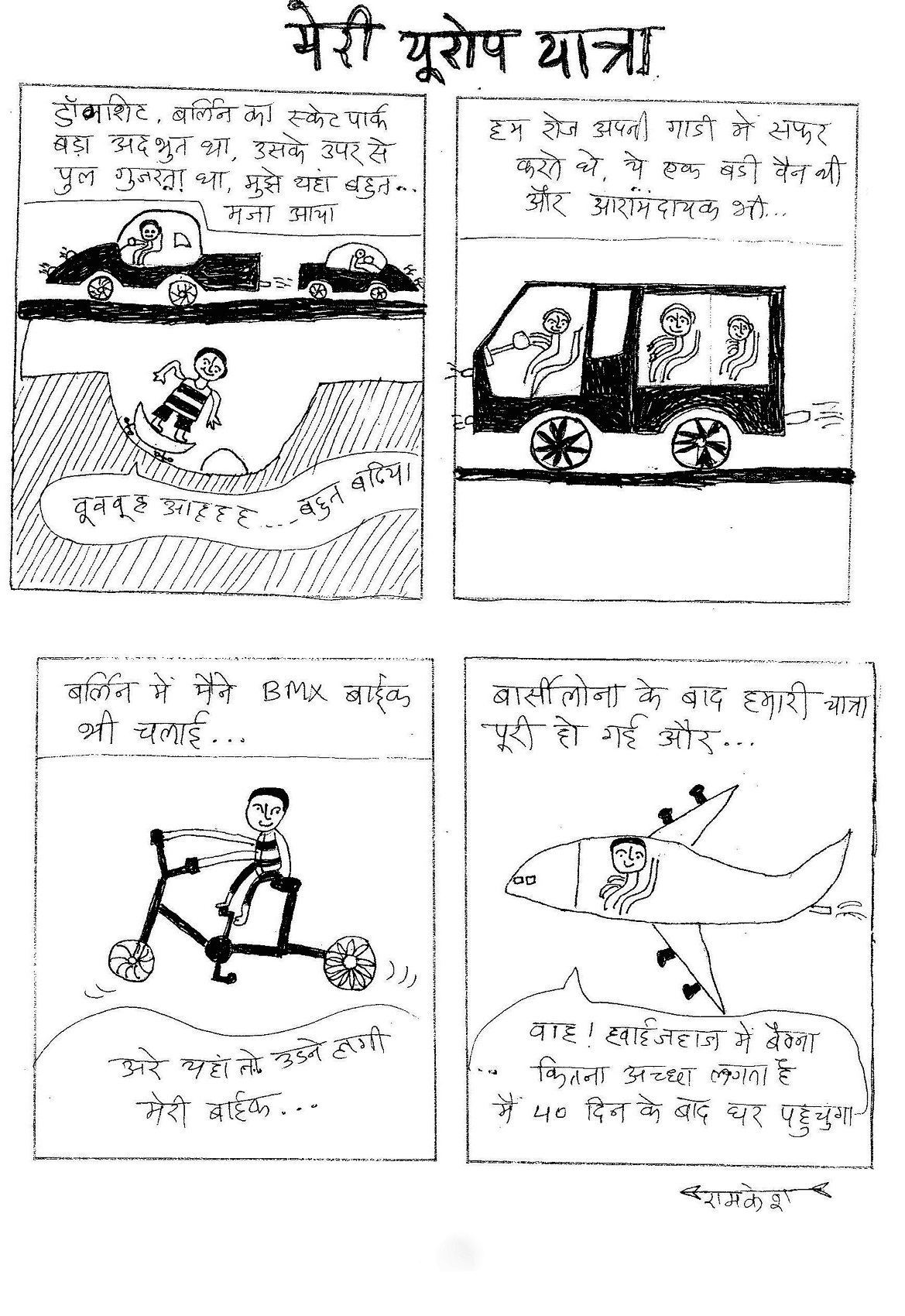

My trip to Europe – by Ramkesh

Scene 1: Dogshit is an amazing skatepark in Berlin. A bridge passed over it. I really enjoyed it there. “Who Aaahhh …Very nice!“

Scene 2: Everyday we traveled in a van. It was a big van and very comfortable.

Scene 3: In Berlin, I also rode a BMX bike… “Oh, here my bike flying!”

Scene 4: Our journey ended in Barcelona and …

“Wow! It’d so nice to sit in the plane. I will reach back home after 40 days”

Ramkesh Gond “shredding” Janwaar Castle. Photo by Vicky Roy.

A Day In The Life Of Ramkesh1

Ramkesh Adivasi / Avneet Sharma

“Hi, my name is Ramkesh, I am in 4th standard and I am ten years old. I have one younger brother and four elder sisters. I wake up at 5 o’clock in the morning; I freshen up myself, and fill water buckets. I head to Janwaar Castle skatepark carrying my skateboard, notebook and a pen. First, we learn English in the Bamboo House, then we do skateboarding, play with frisbee and later learn to play football. I go home around 10 o’clock to have breakfast. So, I go home to have breakfast and afterwards I help my mother with household work. We collect the leaves of a tree called ‘Tendu’, the leaves of Tendu are used to roll ‘Beedi’ (thin Indian cigarette), also it bears a fruit which we villagers eat. After making bundles of Tendu leaves, there is a house in our village where me and my mother take them. The person there puts it into our account – in a notebook through which we get to know how much money we earn per collection. From this house, the leaves are taken to Panna. When it turns into a large sum of money in the notebook; either we buy basic necessities or we waive off our previous debts. Some money is deposited in our bank account as well.

Housework is done and it is time for me to roam around in the village. There are some mango trees in the village. I use my ‘Gulel’ (sling) to pick them. Then I cherish mangos. Sometimes, I play ‘Chiranga’ (marbles) with other kids. Almost half day passes by doing all this and it is time to head home to have lunch. I eat lunch at 2 o’clock. Around 4 o’clock, it is time to hit Janwaar Castle again and practice some new tricks. Exhausted and full of sweat, I go back home; make my bed and lie down.

Meals for breakfast and lunch are mostly the same every day. We eat basic food like lentils, seasonal vegetable curry and rice. Not so fancy food. For dinner, most of the time my grandfather hunts down birds like ‘Titar’ when he take our goats to the jungle. We eat wild pigs as well. If he is unlucky to get something from the jungle, we eat the same rice, lentils etc. During weekends, we eat chicken sometimes. I used to drink milk when we had cows but we don’t. Actually, we can’t afford it anymore. My father had an accident once when he was going to Panna on his tractor and since then, he is on total bedrest. We have consulted many doctors and have tried many expensive medicines but nothing has helped him to get out of the bed.

I like skateboarding and I want to continue it further. In the beginning, I used to see other kids showing off their new tricks. Everybody was getting the new buzz and was ahead of me. Slowly and steadily, I gained confidence that I can do it! I wore pads and put my foot on the board for the first time. My philosophy is simple ‘Conquer your fear or your fear will conquer you’. I have no fear. I can do a drop in from anywhere. You present me a challenge and I will do it!”

Two Girls – Two Worlds2

Ulrike Reinhard

Abhilasha is 22 years old. She comes from a very traditional Hindu family. She has the face and body of a beautiful young woman – still she very much acts like a teenager. Naive. Innocent. Frivolous. Abhilasha has one elder brother and two younger sisters. Her elder brother and her parents have decided that she shall be married early in 2018. She says: “I don’t want to marry now. I don’t even know why I am marrying. All I know is that my future husband’s family is a very nice family, and that he is a good person. He doesn’t get involved in fighting. If someone walks down the wrong path, he doesn’t get involved with that person. I’ve talked to him once or twice. He is the brother-in-law of my cousin. He will come in a few days, then I’ll talk some more.” She doesn’t know much about her future role as a wife either. She says, I just take care of the home. “I try to do a lot of things but I am not able to do them all. I want to learn everything I can, but the problem is I cannot even go out. In the new family, I’ll try to get even better at stitching. I’ll never give up my sewing. I love my machine!”

One year ago Abhilasha got a sewing machine and she taught herself how to use it. And she became really good in stitching. She says that the sewing machine has changed her life.

Esha is 19 years old. She was born in Chhatarpur, Madhya Pradesh, and raised in Panna. She is the only kid in the family – her mother is a college professor and her father a business man. After completing 8th grade in Panna she went to a girls boarding school in Gwalior – THE education town in Madhya Pradesh. Only recently she finished high school. Esha just applied for various colleges in the United States. Her dream is to study computer sciences with a touch of business at Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania. She is trained in Indian classical dance. She says she spent her life so far in splendid lifestyle – and she thought that this is what she was yearning for. If she goes out in Panna, a servant is always with her. She never walks alone.

Her father took her to Janwaar in December 2016 for the first time. Since then she keeps coming back – always with a car and a driver. Most of the time it’s her dad accompanying her. She is teaching the kids English and helps me once in a while with translations and administrative stuff. Which is a great relief. This is how she met Abhilasha. Esha is wondering:

Abhilasha Yadav (left) and Esha Teware sitting inside Abhilasha’s house. Photo by Vicky Roy.

“It astonishes me that a girl like Abhilasha can enhance her ability of stitching under ‘such circumstances’. When I look back in my life and see all the opportunities I had then I wonder how far better Abhilasha could do if she had those privileges. Abhilasha is continuously struggling since 22 years. She grew up in an environment where she is only a voice of no importance. Where girls are treated differently than boys. Still, she is managing to intensify her passion for stitching. Not only the hide-bound family but also the economic conditions she is living in don’t allow much of splendour. This made me think. What if I didn’t had the wealthy background of my family? Would I’ve been able to become what I am today? …. Most likely not!”

Abhilasha has no say in what determines her future life. She is the object of negotiations between two families when it comes to her marriage – it’s the simple and very basic question of dowry. The elder brother is supposed to close the deal. Abhilasha doesn’t talk much with him. She would love to see him work instead of just hanging around the village. But there is hardly any work. She also says that she envies him: “I am not allowed to go around the village like him. I am not allowed to go to Panna. It feels very bad”, she adds. Nevertheless she would never ever speak up against this dire situation. Because hers is the role of a girl in very traditional Hindu society. This is what her life is meant to be.

One day I was sitting with Abhilasha, her two sisters and their mother in front of their house. We were talking about Australia and why Abhilasha wasn’t allowed to go. There wasn’t even the glimmer of a hope that she would be allowed to join two other girls from the village on our trip. The brother said: “In my family no girl will leave the house before she gets married!” The hideous and for me truly incredible reality is that what Abhilasha’s brother is saying is that if she would leave the house, she couldn’t be married anymore! Welcome to the 21st century!

But back to our conversation in front of the house. Abhilasha’s mother said to me: “Look at her two younger sisters, their situation is even worse. They are not allowed to go to school in Panna (both of them have passed the 8th grade and in Janwaar school ends there so to continue they would need to go to the next bigger town), all they can do is get water from the water pump.” And she points to the pump 150 meters away from the house. When I asked her why she doesn’t do anything about it, she only shook her head helplessly. Meaning, I’m powerless, what can I do? Not even a glimmer of hope that she would say something. Beyond her mind. Beyond her imagination. I got angry and had to leave.

Even Esha can’t really grasp why rural and urban make such a difference and she keeps thinking …. “Me and Abhilasha belong to the same culture but our different living standards seem to determine the leniency zones our families allow us. In Abhilasha’s case it might be the social barriers prohibiting her to attend schools — poverty, compulsions of older girls in families having to look after the home. The conception or misconception that girls do not need education or what is taught in schools is irrelevant to them was one of the reason that Abhilasha was allowed not to study after 8th grade. This is so unfortunate to know that parents see limited (economic) benefits in educating daughters. While I was and am given enough time, money and support by my parents, Abhilasha had to stay back home once she attained puberty. Her mother said: ‘Abhilasha must be protected until she gets married!’ Where and why this difference exists? Maybe it’s the lack of education within the families or it can be the matter of the difference in the areas we live in. I can not figure it out!”

For Esha the world is wide open. All Abhilasha can do is to see the skatepark from her house. She says that it looks very beautiful: “Whenever there is a new visitor at the skatepark, the other children tell me and I sometimes I sneak out and go and see what’s happening. I feel very happy about the skatepark. No one used to come to our village. Everyone thought the village was very bad. But ever since the skatepark was built, new people have started to come. We have a homestay here. So sometimes people stay in our house. We get to meet so many new people. I feel very happy about it. And now I feel nice in the village.” Esha looks at the skatepark as the binding factor for all the kids in the village. She says: “In Janwaar I’ve met a lot of masters in their very own ways. Many kids are top-notch – and all of them have started their journey from skateboarding and found their expertise in different fields as well.”

I’ve been talking with Abhilasha quite a lot over the last few weeks. I feel she is a very sensible young woman. Mannan, my colleague, asked her once if she has dreams. “I have a lot of dreams. I don’t think they’ll ever get fulfilled,” she said. She didn’t say though what her dreams are – she kept it secret: “Whatever I tell, there’s no chance of anything ever getting fulfilled.” Yet there is a slight glimmer of hope – she said that the sewing machine which we gave her has changed her life. “I feel very good. It feels like there is a new beginning in my life. I feel very happy about it.” And even though she might not be allowed to take her machine to her husband’s house, she insisted and repeated energetically that she would fight for this!

And this is exactly what Esha admires: “Abhilasha carries the power of acceptance, which I don’t have. No matter what happens to her I always see her smiling. Despite all the barriers life is confronting her with, she manages to work for herself and she does what she loves most …. stitching! Currently she is making bags for the book you are holding in your hands. Her extraordinary nature makes her one of my favourite girls in Janwaar. The respect and friendship she gives me is something which I can not describe in words. I feel so connected with her. Maybe it’s because we have the same names – Esha means wish or desire and Abhilasha is the Hindi word for both!”

Yes, Abhilasha smiles a lot and seems to be happy. “Anything can give me happiness. If someone tells me that their work’s been done, I feel very happy. They don’t even have to be from my family, even then I feel happy.” But she also adds that she does cry sometimes: “Anything can make me cry. If someone says something bad, it makes me cry. Once even you said something in loud voice so I went back home and cried. If someone went for some work, and it didn’t happen – this makes me sad. When I am sitting alone, and I remember someone who is in some trouble, it makes me cry. I think a lot. Sometimes if a sad thought gets in my mind, I don’t sleep all night.”

She says all this smiling, but there are tears in her eyes.

Appendix

When we were in the finishing process of this book, I had a long conversation with Abhilasha’s family. Her parents, and especially her older brother Rakesh, had refused to give their permission for her to join two other girls from Janwaar on a trip to Australia in March this year. There was no discussion just a flat, forcible and very final NO! Her brother said: “In my family no girl will leave the house before she is married!” Period.

True to our mantra that we don’t take “no” for an answer, I took my chance on this warm sunny morning in January. Abhilasha’s father had invited me to the house because he was expecting some forestry officers to come and he wanted me to show them the skatepark. And while we were waiting my opening came. I got them all to sit down and asked why they treated their daughter differently from their son. I explained the impact this journey could have on Abhilasha’s personality and how it could affect her sewing. And I was surprised – we were actually having a conversation and I felt that her mother wanted her to go more than anyone else. Even though she didn’t say a word, she was sending out strong vibes. Which was very surprising to me.

Details

- Seiten

- Erscheinungsform

- Originalausgabe

- Jahr

- 2018

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783955950705

- Sprache

- Englisch

- Erscheinungsdatum

- 2018 (Februar)

- Schlagworte

- Janwaar Castle Skateboarding Rural Changemakers The Barefoot Skteboarders Janwaar